Nietzsche Joins the Party

In which, not really having had a summer holiday, due to COVID etc, I continue working on R13, as I am now naming it as a shorthand.

Schematic chronology of R13

This will be ongoing – need to establish a proper chronology with R13/CERFI events mapped against Foucault, Deleuze, Guattari etc and State events. [See Chronology]

-

September 1971 – Response to offer of funding – Drafting of Chapter 1 ‘La Ville-ordinateur’

-

May 1972 – discussion Guattari, Fourquet, Foucault (pp. 27-31)

-

[June 1972?] 6 months of funding for exploratory research (the key questions are: Is there a specificity to the urban? What is meant by ‘Genealogy’?)

-

July 1972 publication of Les Temps modernes issue Nouveau fascisme, nouvelle démocratie

-

September 1972 – discussion Guattari, Fourquet, Foucault (pp. 27-31)

-

October-December 1972 ‘la toupie folle’ – intensive drafting of texts

-

October 1972 – ‘regulation’ of ‘Ville-métaphore’ (Chapter 2)

-

October 1972 – Marie-Thérèse Vernet-Straggiotti goes on holiday

-

November 1972 – ‘première mouture’

-

November 1972 – drafting of Chapter 2

-

Arrival of FHAR adherents

-

March 1973 Publication of R12 Trois milliards de pervers

-

December 1973 – Publication of R13

Notes on Chapter 4

Chapter 4 – ‘La Formation des équipments collectifs’ is announced in the preface as inaugurating a change of object and method; confronting collective equipment head on, and incorporating genealogy. This is where the influence of Nietzsche’s Genealogy is most explicit, although previous chapters include references to it. The first section of the chapter is titled ‘Nietzsche se met de la partie, et en change le cours’.

It makes sense then that the chapter begins with a long quotation from the Hildebrand and Gratien translation of Nietzsche’s Genealogy, which we can recall had been published in May 1971 as volume 7 of the new complete works established by Giorio Colli and Mazzino Montinari under the direction of Deleuze and Maurice de Gandillac (see Nietzsche dossier). The quotation comes from Section 12 of the ‘second dissertation’ on ‘guilty conscience’.

The key idea here is that the notion of utility which is invariably used to explain, for example, the function of punishment, is a retrospective interpretation on the part of a superior power in view of subjugating and dominating, and which obscures the previous usages. Goal or aim and utility are rather symptoms of a will to power which has ‘captured’ (s’emparé de) something less powerful.

The first point made in R13 is that this view is radically different from the Hegelian conception of history, and from its Marxist inversion. A comparison is made via a quote from Hegel’s Phenomenology of Mind, in its 1939 translation by Jean Hyppolite: the truth is its own becoming… the problem this conception poses for the R13 group is that the ‘truth’ of collective equipment would always be supposed as original, and as ultimate resolution. Any discontinuities in the history of collective equipment would be mere mediations of negations in their self-becoming. There is no origin, write R13, but rather ‘coups de force’.

‘Function’ is thus redundant, and collective equipment cannot be explained by usage within a ‘system of needs’. This is a major insight or provocation of R13, which I’d say somewhat subverts the initial brief from the Ministry, - what is the social need or demand for collective equipment? What needs to be understood and brought to light, rather, is the ‘coup de force’ which ‘gave birth to it’ (naissance) as an instrument of subjugation. After Nietzsche, ‘use’ must be seen as an effect which has imprinted on collective equipment the meaning (sens) of a function. The Nietzschean term interpretation is slanted towards the Deleuze/Guattarian terms of inscription and coding, or more precisely, collective equipments are inscribed as instruments of coding and exclusion of free social energy.

[The later discussion with Guattari suggests that this schema is too simplistic – collective equipments not as instruments of coding, but effects, again, of a more anterior axiomatic].

Along with the system of needs, what is also criticised is the concomitant idea of a Subject (social or individual) of these needs, and classical economics is supposed guilty of such a postulation. Moreover, the idea of an ‘unconscious’ subject of needs, or who needs, is no less transcendent and to be rejected.

The mode of production of collective equipment (Marxist vocabulary) is distinct, then, from the uses which result from them, or to which they are put. Rather, what ‘coup de force’ or ‘administrative decision’ (suggestive vocabulary here, hinting at the contemporary regime and the research project itself, the Plan) was at stake, and what ‘mobile mass’ or ‘flux of people’ or ‘rebut social’ (social rejects?) was fixed, territorialized, subjugated… What was the event at which or through which desire in the social order emerged and was fixed in collective equipment?

[So here we have again the quite straightforward idea of collective equipment as the territorialisation, the fixing, of social desire, or social flux…]

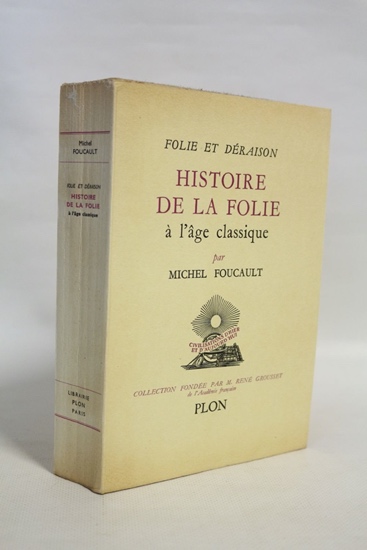

The underlying reference here is to Foucault’s Histoire de la folie, and madness is presented as a paradigm of the ‘wild’ or ‘uncivilized’ social flux which is only utterable or sayable at the moment it is fixed in a structure: ‘faire une étude structural de l’ensemble historique … qui tient captive la folie dont l’état sauvage ne peut jamais être restitué en lui-même; mais à défaut de cette inaccessible pureté primitive, l’étude structurale doit remonter vers la decision qui lie et sépare à la fois raison et folie’. This is taken from the preface to the 1961 (first) edition of Histoire de la folie, published by Plon with the title Folie et déraison, a preface substantially transformed for the 1972 re-edition. The full quotation is as follows:

Faire l'histoire de la folie voudra donc dire : faire une étude structurale de l'ensemble historique - notions, institutions, mesures juridiques et policières, concepts scientifiques - qui tient captive une folie dont l'état sauvage ne peut jamais être restitué en lui-même ; mais à défaut de cette inaccessible pureté primitive, l'étude structurale doit remonter vers la décision qui lie et sépare à la fois raison et folie ; elle doit tendre à découvrir l'échange perpétuel, l'obscure racine commune, l'affrontement originaire qui donne sens à l'unité aussi bien qu'à l'opposition du sens et de l'insensé. Ainsi pourra réapparaître la décision fulgurante, hétérogène au temps de l'histoire, mais insaisissable en dehors de lui, qui sépare du langage de la raison et des promesses du temps ce murmure d'insectes sombres.

The citation from Foucault’s 1961 preface is significant, because it hones in on a sentence elided in the 1972 preface, and one which (according to Jean Khalfa in his introduction to the translation into English of the full text with its variants) was significant for the anti-psychiatry movement, at least for David Cooper in his introduction to the Tavistock Press 1967 translation of the work, who refers to madness as a ‘lost truth’. The idea of a ‘wild state’ of madness, or, as the (progressively downgraded) title of the 1961 edition has it, déraison, resonates well with the idea of nomadic fluxes that are fixed and territorialized by collective equipments, or, in Foucault’s schema, by reason, and later, discourse. The notions of ‘état sauvage’, ‘inaccessible pureté primitive’ and ‘murmure d’insectes sombres’ betray a somewhat romanticized idea of fluid, nomadic desire and expression which the R13 group seem prey to at this point. The R13 team presumably have access to the 1964 10/18 (abridged) edition, and to the 1972 Gallimard full text (with revised preface; the one mentioned in the R13 bibliography and notes) but choose pointedly (and explicitly) to refer to the 1961 preface, which they also highlight in the bibliography.

So R13 extend Foucault’s conception of the event of a ‘partage’ between reason and unreason, and the consequent discourse on madness, to all kinds of flux which ‘only appear decoded and free’ at the point when they are ‘civilized’. But not only this, they continue, all these fluxes and flows are madness itself (it’s not only an analogy); ‘folie’ is the name for all fluxes which are decoded or uncoded, dissociated. The idea here relates to a point in Histoire de la folie, repeated in the ‘medical equipment’ chapter, which is that the ‘hospital’ was, in the pre-modern era, a site for the ‘care’ and then ‘internment’ of the poor, the mad, the sick, etc, i.e. the nomadic, those who were not part of the economy of production and of the family. The ‘hospital’ is thus there to ‘recode’, reterritorialize, fix, normalise, register, represent this quotient of humanity and give them the figure of a ‘person’. The person is a key figure here, which seems to operate as a form of territorialisation in itself.

The discussion moves on to stress the discontinuous character of the ‘coups de force’ which instigate collective equipments as modes of territorialisation. There is neither a social consciousness at work, nor a material logic. It is a question of emphasising and putting into play the differences. No historical dialectic. The succession of ‘formations of equipments’ is accidental (backed up with a clause from the Nietzsche quotation already cited). What is essential is the process of ‘subjugation’ which puts them to work.

Return to Genealogy, and to the earlier quotation. Nietzsche says that the ‘meaning’ or ‘concept’ of punishment is a difficult synthesis of different interpretations; it is a ‘unité difficile à résoudre’ and impossible to define. Presumably because there is no linear cause-effect or need-satisfaction logic to it, but rather an amalgam of uses promoted by forms of instances of subjugation. The presupposition, then, is of a radical heterogeneity of the meaning (concept) of collective equipment, despite its apparent derivation from the time of the Liberation (see later); the questions are: what does it replace, what objects does it designate, in what discursive formations it is present?

This opens up the possibility of a discursive history, or genealogy rather, of the notion itself, which does not remain at the level of vocabulary, since it can have other names…

Mentioned in:

There are no notes linking to this note.